This post concludes a series inspired by the fourth chapter of my new book, Wholehearted: Engaging with Complexity in the Deliberately Adaptive Organisation (April 2025). Building on the organisational model developed in the first three chapters, that fourth chapter, The Space Between, deals with scale-related challenges. The series so far (published first on LinkedIn):

- Leadership as structuring

- Leadership as translating

- Leadership as reconciling

- Leadership as connecting

- Leadership as inviting

- Leadership as representing

- Untangling the strands (this post)

Don’t worry if you haven’t read those preceding articles yet, you can save them for later.

Untangling the strands

If I say that (for example) teams and teams-of-teams exist at different levels of scale, each of those preceding articles identifies 1) some aspect of the relationships that exist between levels of scale, 2) some corresponding leadership responsibility, and 3) some of the dysfunctions that may arise when that relationship isn’t working as it should. I call those relational aspects strands; although they can to some extent compensate for each other, any weaknesses will affect the strength of the relationship as a whole, and with organisational consequences.

It should be plain from this series that I believe in leadership. Also, it may be apparent that behind these articles is a model. I should mention however that in that model, the presence of a manager (or indeed any formal role) isn’t a requirement; what matters is what happens. For it to be maximally applicable – i.e. for this non-prescriptive model to describe as many styles of organisation as possible – it must be capable of accommodating (for example) the self-organising team. It’s a very good thing that it does, and for that and a host of other complexity-related reasons, it would be helpful if it could have something useful to say about organisations that are yet to establish themselves or that exist mostly in the realms of possibility, and regardless of whether the process of formation is directed top-down or emerges bottom-up.

In this model, the strands connect different aspects (traditionally called systems) that you can expect to find present in almost every organisational scope at any level of scale. I say “almost” because scope boundaries may need to be adjusted so that two conditions apply: 1) included in it must be people who identify with it, and 2) beyond planning or managing, it does materially impactful work. The first condition suggests that some of its energy is devoted to maintaining its identity, and the second is a reminder that a functioning organisational scope is more than its manager or leadership team. Ultimately, scopes in this model are defined by their work, not by who is in charge.

Presented in a slightly different order to that used previously, the numbered points below loosely describe for an organisational context the systems numbered 1-5 and 3* in Stafford Beer’s Viable System Model (VSM) [1]. The names in bold for the systems and their corresponding strands are mine, taken from Wholehearted and its core model, the Deliberately Adaptive Organisation. This is my complexity-friendly reconstruction of VSM as it applies to digital-age organisations – not necessarily technology-centric organisations but organisations in which the work of delivery, discovery, and renewal are deeply integrated in ways not envisaged when VSM was created.

- The value-creating work, which as I have said, the presence and range of which helps to define an organisational scope. In a scale relationship, the work of the higher level scope is made up of the work of its lower-scopes (or slices thereof; we can’t afford to assume that scopes are nested in a strict hierarchy). As explored in the structuring article, not only does that imply some organisational structure, it’s important that this structure plays well with other structures, most notably that of the scope’s business environment (market segments, suppliers, competitors, etc), and of the wider organisation’s strategic commitments, both of which change.

- Coordinating between people or groups thereof and over the scope’s work and its shared resources, etc, lest chaos ensue. For scopes at each level of scale to be able to do that in their own language, some translating of progress, issues, performance, etc between levels of scale will be necessary. You can’t impose the language of the boardroom onto the team, or vice versa – certainly not in the general case, and rarely in practice either.

- Organising around current commitments and steering in the direction of goals. Here, the reconciling strand ensures that between and across scales, the commitments of related scopes remain coherent in the light of new information or changes to higher-level plans.

- Strategising, whereby the scope makes sure that it always has options, staying ahead of the game when the game may be changing. Run out of options, and it’s game over! Its corresponding strand, inviting/participating, ensures that the right people are in the room for these conversations.

- Self-governing, keeping operational and strategic activities in appropriate balance and acting as a filter on options that “just aren’t us” – at least until such time as self-identity is rightfully up for challenge, a pivot being in order, for example. The corresponding strand here is identifying/representing, which attends to wider coherence on identity-related matters such as purpose, values, and ethos. If a scope does value-creating work and you identify with it, it almost certainly has this system, the first one, and all the others in between, hence my two preconditions on scope boundaries.

- Finally, contextualising, making sure that operational and strategic decisions alike have the context they need – and the timely connecting of people between and across scales necessary for that to happen beyond the established routine. The issue here isn’t only the obvious one of what happens when context is lacking and bad decisions are made as a result, it’s that no formal structure or processes can eliminate the problem, making this an ongoing challenge.

Why does any of that matter? Straightforwardly, if at some level of scale any of those systems aren’t working well, that’s a problem. More powerfully, if the relationships between systems aren’t working well, that’s a problem too, even if on their own terms, the systems involved seem well-designed. Relationships within a level of scale are beyond the scope of this article (see Part I of the book for that), but it’s true between scales too. How then do you understand the intricacies of those inter-scale relationships and any dysfunctions that may arise therein? One practical way is to approach them a strand at a time, which is what the abovementioned Chapter 4, The Space Between does.

How not to scale, and a remedy

Scaling an organisation is one of those problems for which the common and seemingly obvious answer (at least the one that is easiest to formalise, package up, and sell as an off-the-shelf solution) is the wrong one. You don’t just start with the organisation’s top-level strategy, turn it into a work breakdown structure (WBS) and a parallel hierarchy of objectives, allocate out the work (mapping those structures to the organisation structure), monitor the work, and adjust plans top-down as problems are encountered. Elegant as that may sound (and perhaps attractive to the control-hungry or those with centralising tendencies), the result will be that too many of the problems it will encounter will be dealt with by the wrong people at the at wrong level of organisation and at the wrong level of abstraction. It risks the combination of bad decision making and overwhelm – horrible enough, and with the potential for it to spiral into something worse.

Let me go further. The idea that an organisation’s response to scale-related challenges should be to roll out a process framework is absurd – a sledgehammer not to crack a nut but to make an omelette! Your approach should be not process-based but organisational. And participatory too (or more technically, dialogic and generative [2]):

- Together, make sense of your issues (the model is your lens on the organisation here), and prioritise them

- For the most important of those, and without limiting your solution options, articulate richly what “better” would be like – what stories you could tell “in the Ideal”, of relationships in “healthy and productive balance”, for example

- Identify what stops those stories and what outcomes those obstacles impede

- Invite solution ideas for the stories, obstacles, or outcomes that participants are most drawn to

- Test the best of those ideas

- Monitor progress, again in terms of outcomes – not only those that prompted solutions, but outcomes that indicate meaningful progress, outcomes that tell you when you’re winning, and outcomes that organise all the others – all of which may prompt more solution ideas as needed

- Work toward each affected (and self-governing) scope at every affected scale doing their own monitoring, steering, and strategising in their own language, the right people in the room

What more could you want of an organisational strategy? It’s engaging, highly testable, and doesn’t risk too much on monolithic solutions. It’s based on well-tested and complexity-aware theory, and on 21st-century practice. It puts governance and decision-making in all the right places. It helps you make progress on a broad front, so that you can meet your challenges well. Not a sledgehammer to make an omelette, but an organisational approach to organisational challenges.

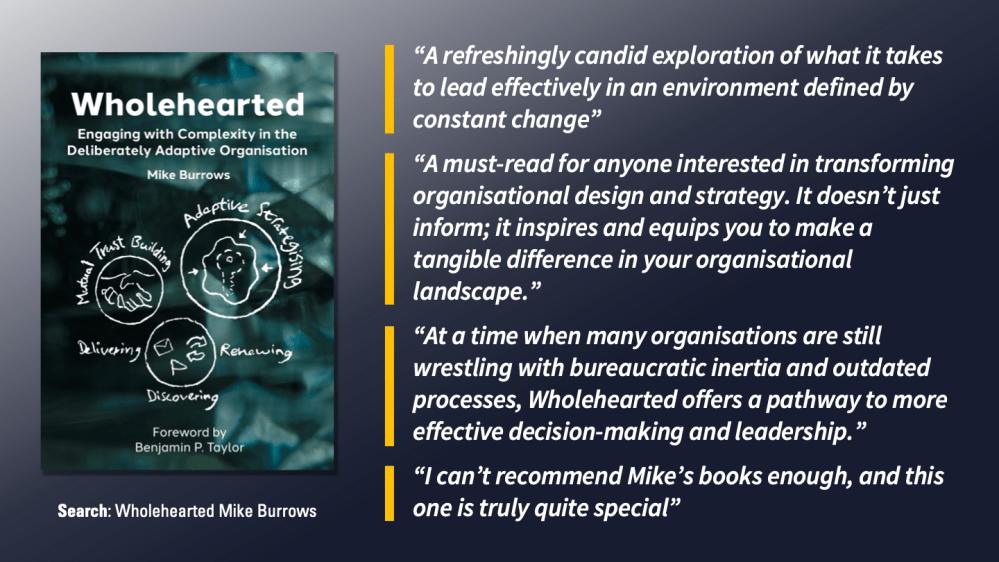

The book

You can find Wholehearted: Engaging with Complexity in the Deliberately Adaptive Organisation (April 2025) in both print and Kindle editions on amazon.co.uk, amazon.com, amazon.de and other Amazon sites around the world. The e-book is also available on LeanPub, Kobo, Apple Books, and Google Play Books. Enjoy!

Notes

[1] The identification of system 3* (“three star”) in Stafford Beer’s The Heart of Enterprise (1979) broke the numbering system established in his earlier book, Brain of the Firm (1972). Or at least it seems to; it can instead be interpreted as system 3 trying to do the impossible, to be in two places at once. No wonder then that the context challenge never goes away! See Chapter 3 of Wholehearted, which for those most interested in the theory is also the chapter in which VSM and the Deliberately Adaptive Organisation are reconciled.

[2] See my 2024 book (a commission for the BMI series in Dialogic Organisation Development), Organizing Conversations: Preparing Groups to Take on Adaptive Challenges.

While we’re here

There will be two (and possibly three) opportunities later in the year to explore these important issues with others. Already scheduled, one online and one in person in Bengaluru, India:

- 30 September to 18 November, online, cohort-based – 8 weekly sessions, 2 hours each: Leading in the Knowledge Economy (LIKE) – Autumn 2025 cohort

- 3-4 December, Bengaluru, India: Leading in the Knowledge Economy (LIKE)

I’m also looking into the possibility of running another in-person training in Copenhagen or Malmö on November 3rd & 4th, ahead of the Øredev conference. If you might be interested in hosting that, please let me know. My flights are already booked – the only question is what I do those two days!