Previously: OODA loop takeaways | Next: Wholehearted Leadership in a Complex World

[This post was first published on LinkedIn here – your reactions and comments there welcome!]

What is the Toyota Production System (TPS)? Is it a long list of tools, many with Japanese names – kanban cards, heijunka, andon cords, hoshin kanri, and so on? Or is it an expression of Toyota’s epic, multi-generational pursuit of customer-focused flow, whose practices change as the world changes and as the organisation learns? It’s an important question: the early years of Lean were so entranced by TPS’s surface detail that it failed to grasp not only what produced and sustained it but what would drive its continued evolution.

We can ask a similar question about Scrum. Is it going through the motions of backlogs, planning meetings, daily meetings, reviews, retrospectives, and so on? Or does it seek to paint a picture of a high-performing team iterating its way to product success, goal by goal? [1]

Describe Scrum “left to right”, backlog first, and an Agile fairy dies. Sorry about that! And Scrum is to a significant degree prescriptive. Without the artefacts, events, and roles laid out in the Scrum Guide you’re not doing Scrum. But if, as I have, you have enjoyed the privilege of working on that kind of high-performing, customer-focused team, whether or not you are doing things by the book matters little. And to put Scrum into historical context, for the teams that first inspired the model, there was no book!

Why put yourself through all that pain when you could address scale-related dysfunctions so very much more directly?

Prescriptive models have their place; the better ones capture (without too much distortion, one hopes) what has worked for someone, somewhere. The problem of course is that they tell you to do certain things regardless of whether they actually address whatever problems are most pressing in your context. The larger the model and the more expensive, time-consuming, disrupting, and (above all) distracting it is to implement, the bigger this problem becomes. I’m not against the models so much as their rollout; in the case of the scaled Agile process frameworks, for example, why put yourself through all that pain when you could address scale-related dysfunctions so very much more directly?

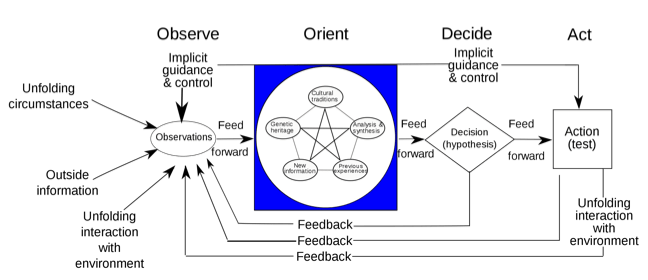

That’s an issue for Chapters 4 and 5 of Wholehearted; here I want to say some more about descriptive models – models that describe what’s there, useful not for what they prescribe but for the insights they bring and those they trigger. One such model is the OODA loop, the subject of my previous article and referenced in Chapter 2, but the book’s main model is the Deliberately Adaptive Organisation, a reconstruction of Stafford Beer’s Viable System Model (VSM), scoped to the digital-age organisation.

It really isn’t something you roll out. It has no prescribed process, organisation structure, roles, or practices. It is descriptive of organisations because it identifies aspects that every organisation must inevitably have to at least some degree, likewise pretty much any organisational scope at any organisational scale that you might identify with. To say that it is useful is an understatement; its undoubted power lies in the relationships between aspects, relationships at and between every scale of organisation that lead to dysfunction if they are out of balance. Working in the other direction, many if not most of the dysfunctions that your organisation currently manifests can be understood relationally.

It might sound abstract to understand a dysfunction in terms of relationships between aspects, but it really helps. You are much less likely to point the finger at some person or group if you can point to a relationship between things you can easily depersonalise. Working at the problem from both ends and from the middle, your solution options are doubled and tripled.

For example, you might follow best practices in the conduct of your delivery-related work and have what you believe to be a world-class system for coordinating that work. But best-practice and world-class or otherwise, if their relationship is not healthy and productive, that’s a real problem. What is the nature of that conflict? That is worth digging into. More than that, it’s worth getting multiple perspectives on it – from those who do the work, those who administer and/or champion the coordination system, and others impacted by the problem. If they can articulate a shared understanding what “good” feels like for that relationship and identify what seems to be getting in the way of that, testable solution ideas can’t be far behind.

The model has enough aspects to be interesting – six “systems” organised into three overlapping “spaces” – and not so many that the model overwhelms, especially if it is taken one space and three systems at a time. Its richness is in its relationships: each system or space has at least two, and that’s considering only one level of organisation. Relationships between scales of organisation (and in practice there are typically many more of those than the org chart shows) are multi-stranded, and untangling those is key to understanding scale-related dysfunction. Understand the problem and you’re already making real progress. Can the same truly be said about the rollout alternative?

Wholehearted: Engaging with Complexity in the Deliberately Adaptive Organisation hit Amazon last month. You can find both print and Kindle editions on amazon.co.uk, amazon.com, amazon.de and other Amazon sites around the world. The e-book is also available on LeanPub, Kobo, Apple Books, and Google Play Books.

[1] ‘Right to Left’ works for Scrum too (July 2018)

Previously: OODA loop takeaways | Next: Wholehearted Leadership in a Complex World