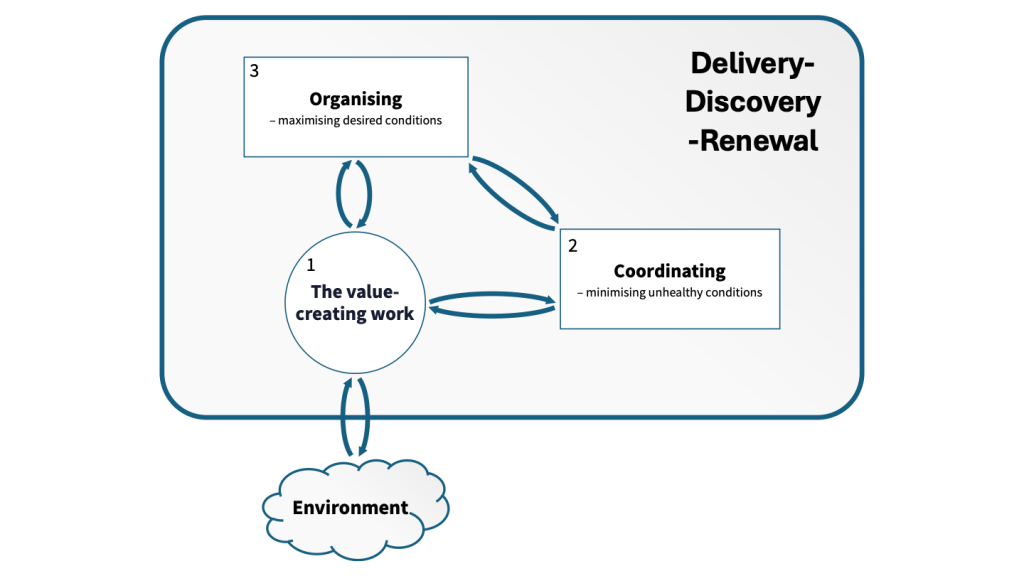

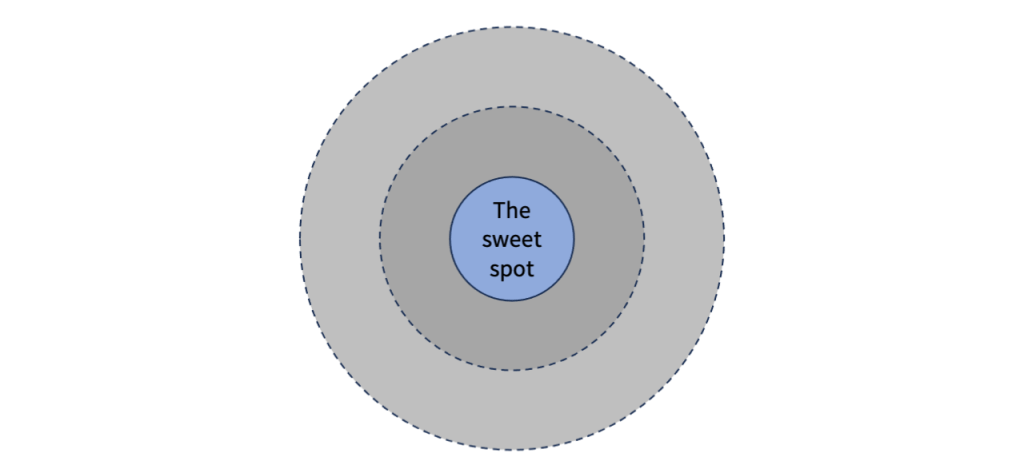

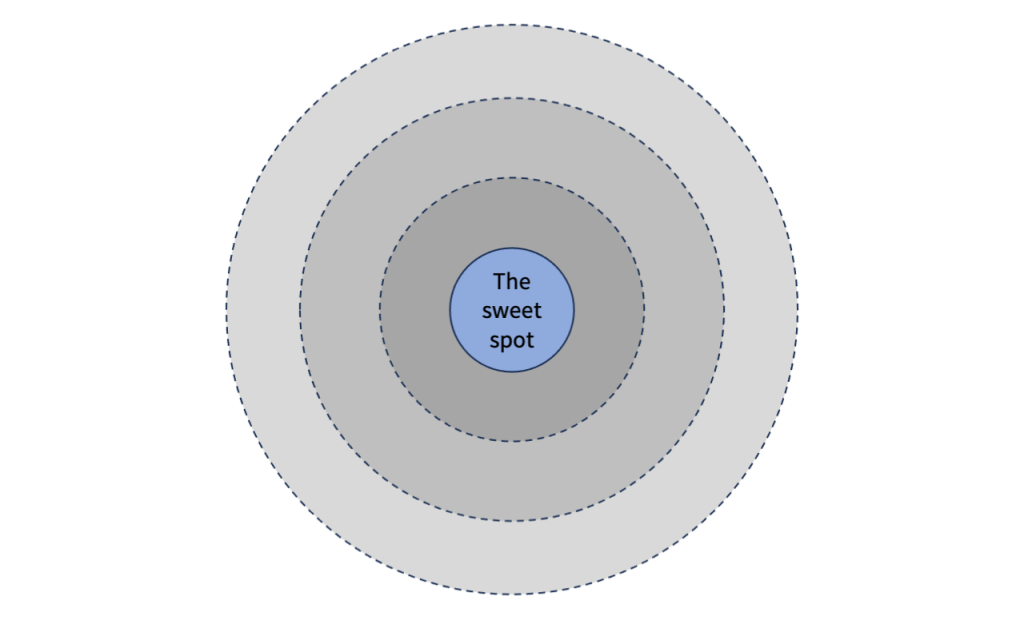

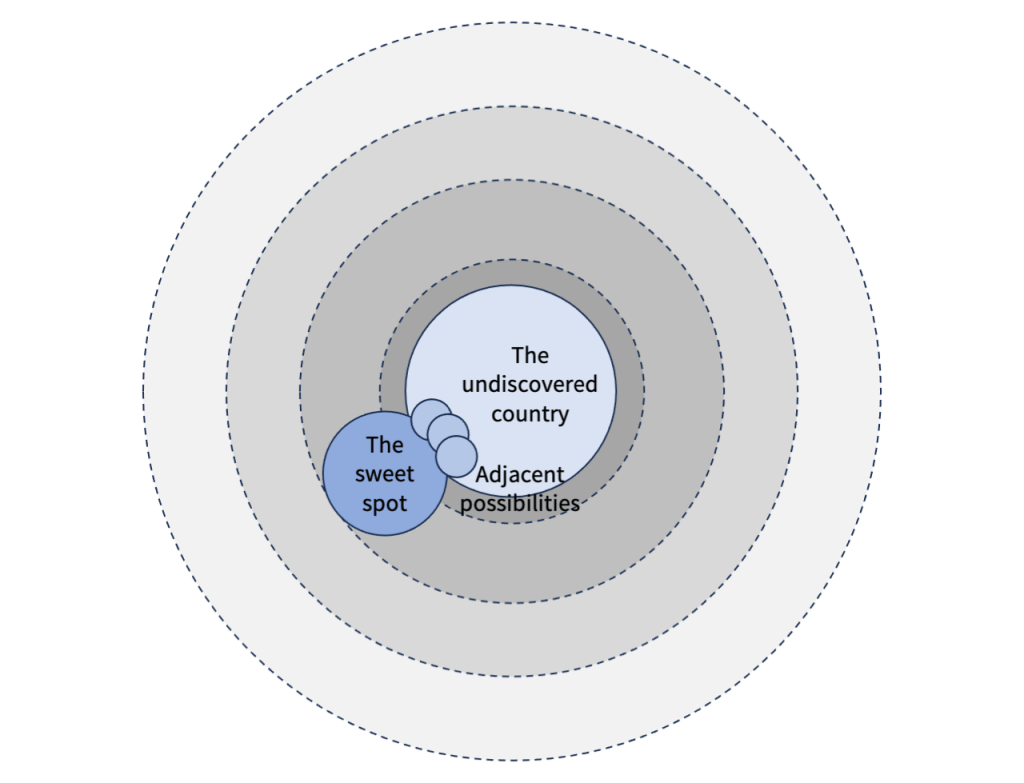

Some context: Measured in chapters (not time, alas) I’ve reached the halfway mark in the writing of my fifth book, Wholehearted: Engaging with Complexity in the Deliberately Adaptive Organisation, completing the first three of six chapters and with those, part I (Business agility at every scale) of two parts. I’ve adapted the article below from a passage in Chapter 1 in which we’re exploring a space I call Delivery-Discovery-Renewal (Figure 1). That space encompasses the productive activity of a team or other organisational scope at any scale of organisation – everything that’s done in the “here and now”, as opposed to, say, planning or retrospecting.

The Delivery-Discovery-Renewal Space comprises the following:

- The value-creating work – delivery-related work (obviously), discovery-related work (making sure that we will be delivering the right things, scouting for new opportunities), and renewal-related work (working on the organisation itself, building and improving the capabilities needed)

- How that work is coordinated – understood very broadly as all the constraints on that work that have any kind of coordinating effect

- How that work is organised – organising around commitments and managing towards goals, another set of constraints on the work

…and their relationships:

- Mutual relationships between systems 1, 2, and 3 above, i.e. between the value-creating work, how its is coordinated, and how it is organised – how they constrain each other, how they inform each other, the effects they have on each other, and so on

- The relationship with the external environment – for the purposes of this article, relationships with customers and users most especially

- Relationships inside system 1 above (the value-creating work) – collaborations, process-defined interactions, structures, and so on

You may recognise there a good chunk of Stafford Beer’s Viable System Model (VSM), and with the mention of constraints, hints of something complexity-related also. The Deliberately Adaptive Organisation model and the forthcoming book cover three such spaces (Delivery-Discovery-Renewal, Adaptive Strategising, and Mutual Trust Building), the relationships between them, relationships internal to them, and the much-neglected relationships between different scales of organisation.

It is very much a relational model, i.e. not a process model but complementary to those, providing them with some sorely-needed theory, particularly on matters of scale. It is easy to engage with, it provides a fresh perspective on familiar things, it translates straightforwardly to a complexity-based perspective, and it can be the basis of a participatory strategy process – all very different from the more analytical ways in which such models are typically used.

In the lightly-adapted excerpt below, we are mid-chapter. You might find it worth giving the above introduction a second read therefore (I’ll refer to Figure 1 more than once). Somewhat in the vein of my January post From Flow to Business Agility (by a huge margin my most-read post of the year so far), we are exploring a key question for the Delivery-Discovery-Renewal space and for the other two spaces:

How might we increase our decision-making capacity?

The Great Rebalancing

One important way to increase decision-making capacity in this Delivery-Discovery-Renewal space is to move away from people serving the process and toward the process serving those who do the work. Some clear signs of success:

- Routine work can be done with negligible overhead

- Coordination problems – contention, overburdening, starvation, and the rest – are seen not as facts of life that people must simply endure, but as symptoms of something systemic that can and should be addressed

- In non-routine situations, appropriate courses of action are made no harder than necessary by, for example, bureaucracy or overly restrictive policies

- Those doing the work have appropriate control over their working environments, and that agency is seen as a potential source of innovation

Each of those reflects some change in the balance between the elements I identified in the introduction to this article, most especially between the value-creating work and how it is coordinated (systems 1 and 2 respectively in Figure 1 above). Taken together, they remind me of the Agile manifesto [1] and, in particular, the first and most famous of its four “this over that” declarations: “Individuals and interactions over processes and tools”. The remaining three declarations can be understood in a similar way, i.e. as representing a sometimes radical rebalancing of relationships inside the Delivery-Discovery-Renewal space.

“Working software over comprehensive documentation”: If we’re staying strictly within the Delivery-Discovery-Renewal space and focusing on the work rather than the thinking behind it, this declaration impacts mostly the balance between upstream and downstream activities. This idea has consequences in many spheres outside of technology development and the book will develop it further. Here though, let’s understand it in manifesto terms.

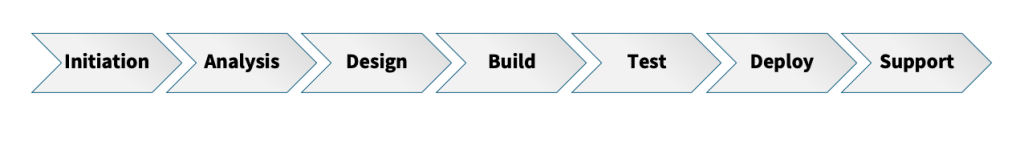

The 1990s, the context in which Agile arose, saw the peak of the linear project model. Technology projects proceeded in a sequence of phases (see Figure 2 below for an example), and because activities were separated in time, those upstream-downstream relationships barely existed. And at such a cost! As projects moved from one documentation-heavy phase to the next, the emphasis was on demonstrating that the latest work conformed to expectations set in preceding stages, not on establishing whether those expectations were based on accurate assumptions. When those assumptions were about the behaviours of users and people-based systems, they would often prove unsafe, but by the time they were invalidated it was already too late.

The remedy: upstream and downstream activities no longer in separate phases but tightly integrated in an iterative or continuous process. With people from different disciplines working closely together, feedback could come in days or less, not the weeks, months, or longer that it took previously. In support of those collaborations, documentation would become much more granular, produced no earlier or later than needed (i.e. just in time), taking perhaps the minimalistic form of user stories [2] or job stories [3], describing not whole projects but very thin slices of functionality – specific usages of individual features. Given an appropriate sequencing of these small but still individually useful deliverables, an incomplete but still meaningfully useful product could emerge quickly. With more time, and perhaps over an indefinite period (funded not as a project but as a product line), it could evolve into something fitting.

The genuine documentation needs of developers, customers, and end-users never completely went away, and there remains the responsibility of the Delivery-Discovery-Renewal space towards its future self. Pity the poor person who, a year from now, has to understand the design decision you made today or debug the code that you’re writing. Perhaps you owe it to them to leave at least some clues, not to mention that this poor person might turn out to be you! Working in the here and now, when the creation of those usually very small pieces of documentation is an integral part of the development process, a more maintainable system results. There remains a need, however, to keep that effort proportionate to its value, an issue outside the “here and now” and the province of the Adaptive Strategising space.

“Customer collaboration over contract negotiation”: The obvious rebalancing here is away from an adversarial relationship that makes change difficult and increasingly costly as it is delayed, and towards a partnership relationship in which risks and benefits are shared equitably and managed cooperatively. The benefits in terms of decision-making capacity alone are enormous, and I have first-hand experience of it working wonderfully in surprising settings.

Before the launch of the UK’s Government Digital Service in 2011, who would have thought that working on a government project as part of a mixed team of staff and consultants could be a truly special experience? As the interim delivery manager on two of GDS’s ‘exemplar’ projects, I experienced exactly that. There were two customer relationships there: the supplier/government relationship and the government/citizen relationship. By far the more important relationship there was the second, and the abiding principle was “Start with needs: user needs not government needs”. That was more than a slogan. We lived by it, and projects that couldn’t demonstrate it would find themselves in trouble.

Of course, beyond the neglect of user needs there are other ways in which the customer relationship can become dysfunctional. The rapid growth of the attention economy, the asymmetries involved in the handling of personal data, and the rise of AI have combined to create a new issue: the technology/user relationship becoming exploitative to the extent of causing real harm. Unlike the Agile revolution, I don’t see the technology industry solving this issue itself; it has become a matter for governments.

One cause of these problems is that the customer and the user are often not the same person. A sponsor paying for a system they will never use isn’t as troubling as an advertiser paying for access to data the user regards as private, but their product teams ignore the user at their peril. Users have untapped expertise, and how they interact with the product has a lot to teach the product team. Even the bad guys know that they need to make their products usable! Again: software cannot be said to be “working” if it fails to meet user needs, and if that needs to be expressed contractually, so be it. Better still, get users as close to the team as you can manage, even part of the team where that’s possible.

“Responding to change over following a plan”: This is the last of the Agile manifesto’s four “this over that” declarations. For the most part this one belongs with the Adaptive Strategising space, but – spoiler alert – the relationship between that space and Delivery-Discovery-Renewal works through what the two spaces share, the scope’s ability to organise (labelled 3 in Figure 1 above). In the “here and now” of this chapter, the relevant capacity-sapping dysfunction is over-commitment.

Overcommitment is closely related to overburdening and one may contribute to the other, but they should not be confused. Overburdening, a coordination dysfunction (system 2 in Figure 1), leaves a team, activity, process, or other organisational scope in an unhealthy and poorly performing condition because it is trying to work on too many things at once. This multi-tasking incurs costs in context switching, quality issues, delays, and frustration. Compounding all of that, additional work in the form of rework. Overcommitment, a dysfunction in organising (system 3 in Figure 1), means that new commitments can’t be made without breaking commitments previously made. Whether that’s the result of taking on too much work, working to a planning horizon that’s too long, working in chunks too large, or working to plans that leave insufficient room for manoeuvre, that’s a different but similarly serious problem. The scope’s capacity for independent action – John Boyd’s definition of viability – is compromised.

Taking those last three “this over that” declarations together, an Agile process matches its commitments to the short length of time it takes to generate useful information. Progress is made hypothesis by hypothesis, goal by goal. Out of an Agile process, products aren’t built fully formed to a design fixed in advance; they emerge.

When I use ‘Agile’ capitalised like that, I’m describing things that can be traced back to the Agile manifesto. In that sense, the forthcoming book is an Agile book per se; its roots are elsewhere. You can see in the above discussion, however, both what’s at stake and what’s possible. This is not to say that all is rosy in the Agile world: my previous books all address the issue of the Agile industry imposing process and practice on people, to the extent that “Individuals and interactions over processes and tools” can seem cruelly ironic at times. Nevertheless, I make the bold suggestion that Agile has been more successful – unreasonably successful – than perhaps its own community realises.

Consider the effect of this Great Rebalancing (or if you prefer, a great shift in organisational constraints) not only on the decision-making and communication capacities of the teams involved but also on those around it. Capacity that previously was consumed by the need to manage teams from the outside has been relieved of much of that burden. Capacity thus freed can be applied to more interesting things. That improves the experience of leadership, increases the quality of leadership, and greatly increases the chances that self-organised innovation will occur not only within teams but at larger scales too. That is what the book will be about: identifying and dealing with dysfunctions at every scale, enabling other great rebalancings, and unleashing thereby other kinds of “unreasonable effectiveness”.

Ping me if interested in tracking progress on the book; some have early access to the manuscript already, and with a view to getting multiple perspectives on it I will be setting up multiple review circles in the coming weeks covering tech, healthcare, education (i.e. universities), faith communities and other voluntary or not-for-profit organisations, and the systems and complexity communities.

See also Leading in a Transforming Organisation in Berlin, London, and Southampton in the list below of upcoming events. Highly relevant! Days 2 and 3 have much the same structure as the book. Likewise, under the heading of Leading with Outcomes, the self-paced Adaptive Organisation parts I & II further down the page below.

[1] More properly the Manifesto for Agile Software Development (2001), agilemanifesto.org

[2] See my favourite Agile book: Jeff Patton and Peter Economy, User Story Mapping: Discover the Whole Story, Build the Right Product (2014, O’Reilly Media)

[3] Another book that I recommend frequently: If interested in job stories and the jobs-to-be-done (JTBD) framework, start here: Bob Moesta & Greg Engle, Demand-Side Sales 101: Stop Selling and Help Your Customers Make Progress (2020, Lioncrest Publishing)

Upcoming events

February

- 18 February, Online, 16:00 GMT, 17:00 CET, 11am ET, Agile Strategy Meetup Group:

Meet Mike Burrows on strategy - 24-27 February, four 4-hour sessions online, afternoons UK time:

Leading with Outcomes: Train-the-Trainer / Facilitator (TTT/F)*

March

- 06 March, London, UK:

Kanban Edge 2025

*TTT/F and (where shown) LIKE events include free one-year membership of the Leading with Outcomes Authorised Facilitator programme, upgradeable to Authorised Trainer at any time. Both of those include access to the video-based Leading with Outcomes training and the full range of Agendashift assessment tools.

Leading with Outcomes from the Agendashift Academy

“Leadership and strategy in the transforming organisation”

Leading with Outcomes is our modular curriculum in leadership and organisation development. Each module is available as self-paced online training or as private, instructor-led training (online or in-person). Certificates of completion or participation according to format. Its modules in the recommended order:

- Foundation module:

- Inside-out Strategy:

- Adaptive Organisation:

- Outside-in Strategy:

Individual subscriptions from £24.50 £18.40 per month after a 7-day free trial, with discounts available for employees and employers in the government, healthcare, education, and non-profit sectors. For bulk subscriptions, ask for our Agendashift for Business brochure.

To deliver Leading with Outcomes training or workshops yourself, see our Authorised Trainer and Authorised Facilitator programmes. See our events calendar for Train-the-Trainer / Facilitator (TTT/F) and Leading in a Transforming Organisation trainings.

Agendashift™: Serving the transforming organisation

Links: Home | Subscribe | Events | Media | Contact | Mike

Agendashift Academy: Leading with Outcomes | Trainer and Facilitator Programmes | Store

At every scope and scale, developing strategy together, pursuing strategy together, outcomes before solutions, working backwards (“right to left”) from key moments of impact and learning.