At least as far as the textbooks go, 21st century Lean is quite a different beast to its 20th century forebear. The best of the more modern Lean literature is now explicit in its recognition that you can’t just take the Lean tools out of one context, drop them into another, and expect the same results. Just because it works for Toyota, doesn’t mean it will work for you. Just because it works in a car factory… I hardly need to complete that sentence!

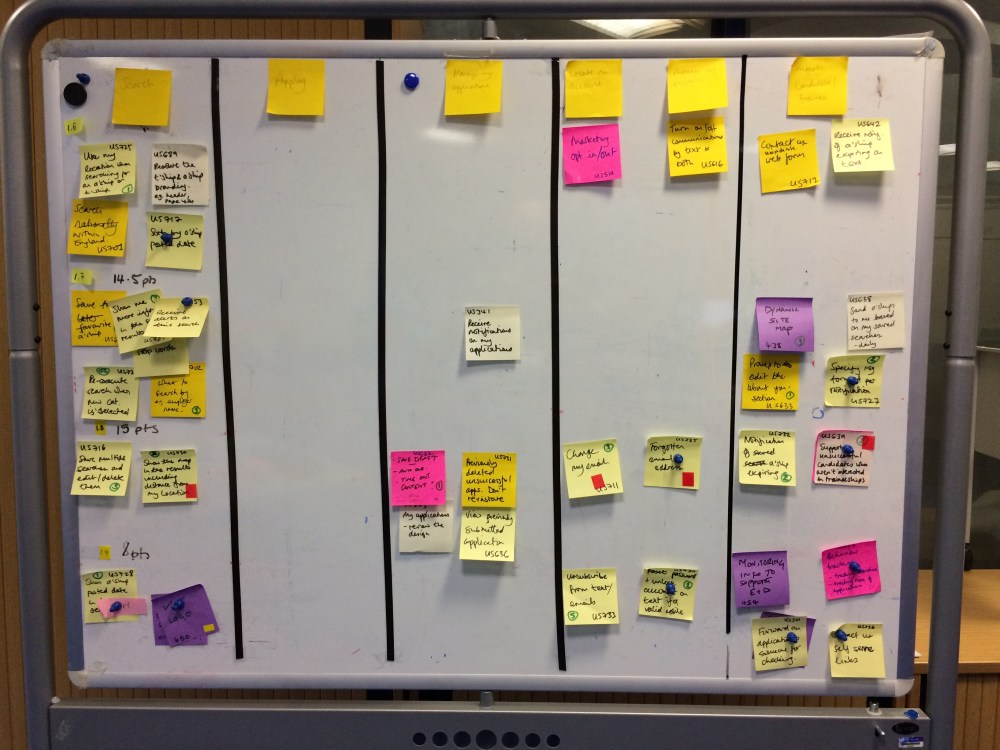

Not unmodified, that’s for sure. The kind of Kanban I described in Kanban from the Inside that works so well for people engaged in creative knowledge work is almost unrecognisable from the canonical kanban systems of the automotive factory. Many of the underlying principles are the same – for example visual management, controls on work-in-progress, the quest for flow – but their physical or electronic realisations are very different. In one, cards move left to right (downstream) on a kanban board to reflect the progress of work; in the other, cards are sent upstream when some downstream activity wishes to signal a need for some just-in-time replenishment.

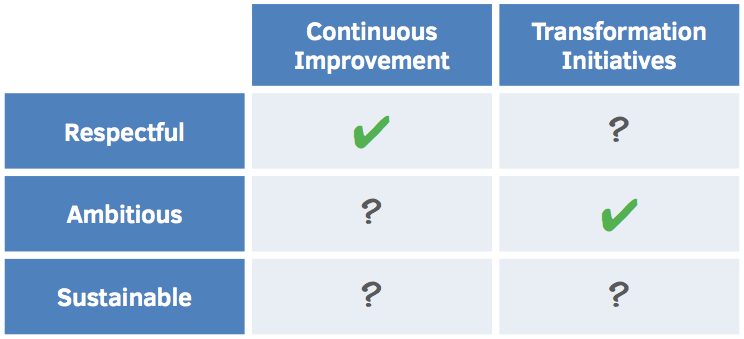

But that’s just technical detail. The best of the 21st century Lean authors have been humble enough to make an even more important admission: even within the manufacturing domain you can’t (as the 20th century writers tried to suggest) transplant the tools whilst ignoring the management systems that guide, support, and sustain them, and still expect good results. An important case in point is continuous improvement (or kaizen, if you prefer). Don’t get me wrong: continuous improvement will always be a good idea. Unfortunately though, it is rarely sustained for long through goodwill alone. Asking your workforce for continuous improvement as a low-commitment way to achieve real transformation will almost certainly result in disappointment, even harm.

We in the Agile community know all this of course – how often do we see retrospectives fall into a state of neglect once the easy changes have been made? Unfortunately, we make it harder for ourselves, and by design! As an end-of-century reaction to 20th century top-down and plan-driven management styles wholly unsuited to the challenges of rapid product development in uncertain environments, Agile rightly sought to wrest control back to the teams doing the work. The unfortunate side-effect: blindness to the power of the kind of internal structures that create regular opportunities for mutual reflection, support, and accountability well beyond the team. How is the Agile team supposed to help the organisation become more Agile when it is determined to live inside its own protected bubble? This is how inspect-and-adapt (Agile’s continuous improvement) runs out of steam. Even at team level it’s hard enough to sustain; expecting it to drive broader change without support is, well, optimistic.

I’m not looking to throw the baby out with the bathwater. I’m not suggesting any backsliding on Agile values. I’m not making the case for 20th century top-down management (in fact quite the opposite). I’m asking that we look beyond the delivery-centric processes and tool (most especially beyond the determinedly team-centric ones) and start to think about what that cross-boundary support and accountability could look like.

In particular:

- What will drive Agile teams and their host organisations to help each other to serve their customers’ and each other’s needs more effectively?

- Where are the joint forums for reflection?

- What mechanisms will provide support and ensure follow-through, even when the necessary changes become more challenging on both sides?

- Where are the opportunities for people to engage seriously in the development and pursuit of organisational goals?

- What skills will be needed to make these things happen?

Outside the Agile mainstream, Kanban and Lean Startup have opinions (if not explicit guidance) on many of these questions. Helping people pay attention to concerns such as these is one Agendashift’s main motivations. Much of Agile however still seems to ignore them, sometimes recognising the need for end-to-end thinking but still wary of “at every level” thinking.

The good news is that these concerns are largely orthogonal to delivery. Agile delivery frameworks probably don’t need to be any bigger than they are today (let’s hope so). Some awareness of organisational context and its journey will be necessary though, and it may mean leaving aside the rhetoric of past battles. Welcome to the 21st century!

Blog: Monthly roundups | Classic posts

Links: Home | Partner programme | Resources | Contact | Mike

Community: Slack | LinkedIn group | Twitter